Embracing Identity: Michael Gagnon's Journey as a Queer Educator in a Conservative State

Teaching While Queer, Season 2, Episode 23

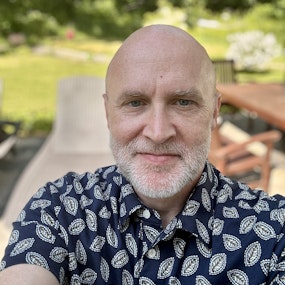

Navigating the complexities of identity in the classroom, Michael Gagnon (he/him), a seasoned high school English teacher, joins us to share his powerful story of growing up queer in a conservative, Catholic family. From the shadows of shame and the height of the AIDS crisis, Michael's journey to embracing his true self is a beacon of hope for anyone struggling to find their place. Our conversation with him is a raw and honest look at the personal cost of authenticity, and the courageous battle for acceptance in the educational sphere.

As teachers, we often walk a tightrope between professional expectations and personal truth. Michael and I peel back the layers of what it means to teach with your whole self on display, examining the emotional trials and the need for supportive environments that do not compromise one's identity. We also confront the political climate targeting educators, discussing the strains of remote learning, and the challenges that arise when controversial topics spill into the classroom. The resilience of teachers under such scrutiny becomes a testament to their unwavering commitment to their students and their craft.

Wrapping up, we delve into the sensitive dynamics between parents, educators, and LGBTQI+ students. The critical role of empathy and open communication is underscored, celebrating those parents who champion their children's journeys. Meanwhile, my own transition from the classroom to podcasting emerges from a desire to amplify the voices of fellow educators during turbulent times. Gratitude flows for the listeners who join us in these conversations, fostering understanding and support for the queer education community. Together, we are reminded of the strength found in shared stories and the transformative power of education.

To be a guest or to hear more episodes visit www.teachingwhilequeer.com.

Follow Teaching While Queer on Instagram at @TeachingWhileQueer.

You can find host, Bryan Stanton, on Instagram.

Support the podcast by becoming a subscriber. For information click here.

Thank you for listening to this episode of Teaching While Queer Podcast! Please help support the podcast by leaving a review wherever you listen to the podcast.

You can find host, Bryan Stanton, on Instagram.

Follow us on Instagram at @TeachingWhileQueer

To be a guest or to hear more episodes visit www.teachingwhilequeer.com.

00:26 - Teaching While Queer

13:39 - Teaching Authenticity and Educator Challenges

21:11 - Education, Politics, and Targeting Teachers

33:35 - Parent-Child Relationships and Supporting LGBTQI+ Students

40:14 - The Importance of Parent-Teacher Communication

49:15 - Teaching While Queer

Bryan (he/they):

Teaching While Queer is a podcast for 2SLGBTQIA+ educational professionals to share their experiences in academia. Hi, I'm your host, Bryan Stanton, a theater pedagogy and educator in New York City, and my goal is to share stories from around the world from 2SLGBTQIA+ educators. I hope you enjoy Teaching While Queer. Hello everyone and welcome to another episode of Teaching While Queer. I am your host, Bryan Stanton. My pronouns are he/ they. Today, I have the pleasure of speaking with Michael Gagnon. Hi, Michael, how are you doing?

Michael (he/him):

I'm well, how are you?

Bryan (he/they):

I'm doing great. Thank you. Why don't you tell us a little bit about yourself?

Michael (he/him):

Well, as you said, my name is Michael Gagnon. My pronouns are he/ him. I am a gay teacher. I currently teach high school English in a suburban district in Connecticut.

Bryan (he/they):

In Connecticut Awesome. I think you're my second person from Connecticut and I love just kind of like expanding my little map as I interview different teachers, so awesome. When it comes to kind of like your own experience, what was it like for you as a queer youth and a queer?

Michael (he/him):

student. It's a long story. It was a long time ago and a long story. So I came of age in the 70s and the 80s so I certainly knew that I was different when I was young probably six, seven, eight not really understanding what that meant until I went through adolescence and realized, oh, that's what it means and I had a lot of trauma growing up. So my part of a very large family. I have eight siblings.

Bryan (he/they):

Wow.

Michael (he/him):

Yeah, mostly there are seven boys and two girls altogether. So and my mother died when we were young. So I was about just about 13 when my mother died suddenly and unexpectedly. And I knew before then and had mentioned to an older brother that I thought I was gay, and he had apparently had mentioned it to my parents, which I didn't know, and then I assumed, as I had mentioned it, I was like, no, no, no, I was just just confused, that's all.

Bryan (he/they):

Yeah, yeah, it's a fleeting thought.

Michael (he/him):

It's a fleeting thought. And then my mother died shortly thereafter and I decided I just couldn't deal with it. I just could not deal with the loss of a parent and trying to figure out who I was. So it was like I'm just going to put it on the back burner, you know, I'm just not going to think about it and get myself through high school and sort of kept to myself as much as possible because I couldn't possibly date someone, date a girl, and think, yeah, to me, it just it would have been wrong. It just didn't never felt right and I felt like I was doing something bad to a girl if I dated her. So I just dated no one and sort of kept to myself. And then it was in my early 20s that I was like I can't live this way anymore and finally decided I really needed to be out. And at that point, when I came out, I came out so as a teenager and as a young person, you know, struggling with the constant feeling of not being a part of something and and I self isolating just out of protection, which left me very much alone, sorry.

Bryan (he/they):

It's all right. We love cat appearances Hello.

Michael (he/him):

So he will be back and forth because it's almost dinner time for them, so, but it was. You know, it was really difficult and it was really constantly dealing with the shame my mother had been a very strict Catholic, my father was not, but my, you know, and so the sense of shame that I felt, like oh, my mother had died, and maybe it's because, you know, maybe it's because of me and all those things that a young person might think when something like that happens, and trying to reconcile those feelings as well, just made it really really difficult and feeling, you know, so separated from everybody and having people, you know, including my own siblings, useless and, and you know, to put me down and it's, oh, you know, you're a faggot and you're this and you're that and sort of having to live through that with my own family, not to mention kids at school. So it made it a really difficult time and a really lonely time for me and you know, thanks, I got through it and I started to come out and made friends and, you know, my whole world opened up after that. So, you know, the whole movement of it gets better If you hold on. It does get better. If you come into your own, you're able to do those things. It does get better, but it was incredibly difficult. And then you're coming of age during the height of AIDS and all of that, and you know all of the hate that went with that and you're terrified to get involved with anyone. You're terrified that, oh you know I'm going to get it and I'm going to die, and that just exacerbated a lot of those negative feelings that you had to work yourself through to eventually come to a place where you finally got accepted. You know, worked on acceptance for myself and who I was.

Bryan (he/they):

Absolutely. Did you always grow? Did you also grow up in Connecticut, or was this somewhere else in the country?

Michael (he/him):

I did. No, I grew up here in Connecticut. It's strange because my father was a blue collar worker. He was a male man. My mother didn't work, so how he managed to raise nine kids on a male man's salary I'll never know. And I was born in Hartford. We had been raised up until I was three in Hartford and then we had to move and for some reason ended up in a fairly affluent town. I don't know how they afforded the house in the town, but you know we were like the white trash of that town. So you know we were the family you point at and go like don't, if you don't do well in school, you're going to end up like these kids. And you know I'll say I probably ended up better than most of them. I have more education than they probably do and used to make more money than they did before I became a teacher.

Bryan (he/they):

I definitely hate those moments when, like parents try to use other people as examples. This is a silly story, but I was at Disney World with my husband like a decade ago, and it started a downpour and we didn't bring our jackets, whatnot. We got back on the shuttle to go to the hotel and this mom was like this is see, if you would have not brought your jacket, like I told you to, this is what would have happened. I was like it was 100 degrees. The rain made me feel real nice. Like, don't use me as an example. I'm like it's just so funny how judgmental people can be just from looking at somebody else and it's something as silly as rain or something as important as like that family down the street. We don't want to be like them, right, and that definitely has to play into like your own sense of self. I think as a young person, because you're not living life in a vacuum, you experience that.

Michael (he/him):

And the amount of shame that you carry from it, the amount of feeling like, oh, we're something bad or something wrong with us. And I have a very good friend today who actually is friends with somebody who grew up in the neighborhood that I grew up in and we all got together at one point and this person was there and she was talking about, like oh you know, do you keep in touch with anybody? I'm like no, I was a miserable experience. I don't you know any friends that I had from high school or the two or three people that I'm still in touch with state, but I'm not interested in anybody else. They certainly were not either kind or chiseled. I said, besides, all your parents used to say this about us, and she was shocked. She was like you knew, and I'm like, of course we knew. It's not like you guys, like your parents were secretive about it. They were very right out in the open. I said what's interesting is none of them ever asked I wonder what's going on in that house, that these kids are maybe a little wild, or these kids are like you know, in what happened, especially after my mother died, like you know, they've just lost a parent and you know, here's this poor guy trying to make ends meet with nine kids and trying to figure it out. It's like, no, you didn't ask that, you just judged, you know, and like that's the way people are. Unfortunately, it really is.

Bryan (he/they):

I find that incredibly disheartening, just like in communities. And it's funny because I was so afraid when I moved from California to Texas that there was going to be so much judgment going on. And Texas is an interesting place because Texans will be nice to your face, they will be kind to your face, and then it will be in closed door conversations where they're kind of talking about you. And we had this group of neighbors that was really fantastic when we first moved in, like the folks across the street treated our daughter like she was a granddaughter. Our neighbors were really great, the neighbors Cattie Corners, who us kept inviting us to parties and whatnot. And then we found out after we moved that they hated us. And like we're talking all about everything that we done to modernize our house and all these things and how they hated us and I was like oh, wow, it's wild, because I think that community is so important and where you live is so important and and you can't just judge a book from its cover Like I live in the Bronx now in New York City and my mom saw a Google image when we were telling her about our house and she was like there's graffiti two houses down. It's like a complete ghetto and I'm here and I'm like everybody's so nice and they're looking out for each other and like there's a true sense of community, and it's like you can't just look at a picture and decide that's what it is. And that's the same situation with you folks. Is that like someone looked at a picture or like a, a moment in time, right, this picture in their brain of a moment in time with you, and was like those are the bad kids you don't want to be like them, right, right, hopefully human nature will get over that a little bit like the comparison side of things.

Michael (he/him):

But I'm sure that's millennium, let's be it in the school environment, that microcosm of of the world, and it's still, you know, I think it's human nature, I think it's. You know, one way to build yourself up is to put somebody else down, um, and you know, to take those differences that you think are less than um and, you know, use those as a way of pointing out like, see, we're on the right side and you're on the wrong side. And I think you know, we see that in every area of you know, our society today, where we're still doing that.

Bryan (he/they):

Yeah, and how do you?

Michael (he/him):

whatever.

Bryan (he/they):

How do you see, uh, your experience as a queer youth kind of informing your pedagogy or your teaching? I? I'm imagine that like not to mention the personal side of things, like your personal life Growing up during the time period that you did. There was a lot of trauma surrounding that as well, because I came of age in the 80s and 90s and so I'm like the tail end of that kind of trauma, but you came of age kind of right in the middle of it. Um, so, as an educator, how do you see kind of your experiences as a queer person, informing how you interact with your students?

Michael (he/him):

I think, growing up and dealing with that shame and having to work through it to become the person you know that I've become, and realizing like there was no purpose to it, that like shame doesn't do anybody any good. It's it's about, you know, when you do actions. It's about responsibility. Was I responsible for them? Was I not responsible for them? You know what role did I plan them? And therefore you know who I am as a person, biologically and physiologically and and mentally. You know the components that go into making us who we are. I, you know, as a youth I wasn't responsible for those. I was in this situation and how I processed them was a matter of my environment and numerous other things. So I think when I became an educator you know I was in corporate America for a long time left to finally become a teacher and because it was what I'd always wanted to do and then, um, start teaching my first or second year in and kids, you know it was amazing to me first of all that students were asking about your personal life, because I'm like I would never have done that when I was like no one asked teachers anything about them. Um, and suddenly they all are up in your business. And so I actually started teaching. My first four years were in hawaii, and so to have students ask, and you know they would ask like, well, you know your girlfriend and you're, you know I'm like, well, what are you talking about? Well, you know the person, you, you, you know, who do you live with? Who do you live with? I said I live with the person I love and I'm like, well, who's that? I'm like that's the person I live with, and I sort of round around where I wouldn't really answer the question and after a couple of years of that, you know the kids would eventually figure it out. You know they put like, oh, that's, that's it, you know. And then, and it was fine, it was like after that it was dropped and it was no Big thing, which was also kind of surprising because I'm like really okay, and the more that that happened was the feeling of like I'm tired of having to either play it blank or, you know, play this game, so that I'm not just saying the truth, um, for fear of my job and for fear of, um, how parents and even students might react with. The fact is, you're free to feel any way you want about it and you know that's what makes this a free country. But I'm also free to be myself. And so I just decided at one point I'm not changing Um pronouns or being general if people ask what you know, if kids ask me what I do at the weekend my husband and I did this and and that's what I'm going to do. And I just Decided to do it. And I was, like you know, both in Hawaii and in Connecticut. I am protected by law, at least for now. Not done would stays that way. Um, but Even if it weren't, I don't think that I could teach without being Just open and and being who I am. It's I. I'm done, being ashamed of it. I'm, I'm done with that part of it. You know, one's going to have that kind of power and control over me ever again. And I don't care what the cost is, because if it cost me my job, it's not a job worth having. So I can't be a good educator. I cannot be Talking to students. You know I teach English and literature. I cannot talk to students about empathy and about understanding perspectives if I'm hiding my own. So it just doesn't work. And so you know, for me that just became the it I was not going to pretend for anybody and you know it. Just it's the way it is and I've had gotten, you know, pushback for that, um from people, from parents and people who didn't want their kids in my class, and I can switch them out. I don't know what to tell you and and I'm thankful that I have To my district or administration credit. They're like no, I mean, you know, that's not an issue to move a student, like he's not in there selling it, he's not in there talking about all the time the kids asked him. He's not going to lie to them, um, and I, you know, I'm teaching a new class in humanities this year in literature and I with seniors and I'm having a really great time and having really open, honest discussions and they ask great questions and I tell them the truth and they're like you wouldn't lie to us. I said, if I can't tell you the truth, I'm going to tell you. I can't tell you because it would jeopardize my job and they have yet to do it, or If they've asked a question that might have, and I I decided to answer it. I just am like we'll see, especially right now, where we have quite the target on us lately. So it's like I'm again, I'm just, I'm done with it. And maybe that comes with age. Maybe you know old enough now, um, that I'm just like I'm, I'm done doing this, like no. This is the reality of the world and we all need to accept each other and you're free to think whatever you want, you're free to not like me for it, but you're here to learn and I'm here to teach and that's what we're going to do and I, you know, generally, the Majority of all the feedback and interactions with students has been really great, you know, which says a lot about the younger generation today, and I hope, hope, hope, hope, hope, hope that they stay that way as they get older and push out all of this. You know craft, that's going on.

Bryan (he/they):

Absolutely. I think one of the things you mentioned that's like it's worth repeating is just kind of if it's a, it's a Excuse me. If it's a job where I'm going to get fired over this being who I am, then it's not a job worth having. And I think that young people Are kind of trained in capitalism that they feel like they have to accept the job and then be at the job For like a long time. And my mentality is kind of like accept the job and if you realize it's not like working, you can look for another job while still having this job. And that's true of educators also. Like you don't have to wait till the next school year. I guarantee someone's going to have a middle-mid-year Contract that they're going to need to fill, especially right now, and it's more worthwhile to keep looking for the place that's right for you than to just kind of Grin them bare bare it, you know.

Michael (he/him):

Yeah, things have been so hard lately. I mean, I, you know, got took the long route to becoming an educator. I wanted to be one ever since I was little and when I graduated high school, my father said why would you want to go into teaching? You'll never make any money. You've grown up. Or like, go, you're good with numbers, you're good with money. Like Go and go into business. So I became an accountant and I'm like, yeah, and I lived in New York and I lived really well and Spent a lot of money and Um, but enjoyed myself and was like okay, and but it was like I was not fulfilled and not happy. So for me, you know, teaching was the minute I walked into a classroom. I felt home, and so the hard part about thinking about leaving it or even going to another school is always the fact like this is where I've. You know, I still feel like I belong here, and yet in the last two years have not felt like it's been easy to connect with students, have felt like I am constantly in battle with parents, which is just exhausting, and with community, and with the community and with community and with politicians, and I'm like I'm just, and even with administration to a certain degree and I'm like I just am Exhausted by it and I actually just had it. You know, I don't know if it works the same way where you teach, but you know you have your um evaluation, um, and so at the beginning of the year you have like the evaluation meeting where you set your goals for the year, so they know what they're gonna evaluate on. So I just had that and I actually told the administrator. I said you know, the only reason I'm back this year Is because I work with a really great department and I have a really great department leader and they're the people I respect. They're the people who look out for me and I look out for them. And right there, the only thing that got me back in this building this year and luckily I'm in starting to enjoy my students again and feeling more connected to them, because for the last two years I hadn't, because of all of the politics going on and the pushback. So, um, you're right, it absolutely if. If that's, that's, that's what makes a difference. And if you can't find it, then at the place you're at, then you need to go and find it somewhere else.

Bryan (he/they):

So I'm not currently teaching when, when we just decided to move to new york city, we are very fortunate in that we had some rental property that we could sell and kind of I could choose and find the job that I Wanted, and luckily I have found one, and you know, I'm just waiting on that paperwork but, um, I have heard from a lot of teachers that this year has been harder than the last, and what's wild to me is that, from a teacher perspective, 2020 to 21 was bad because of virtual and in-person and virtual and in-person Right, and then 21 22 was bad, and then 22, 23 is bad, and now here we are 23, 24. It's like every year is getting worse since we all went to isolation in the pandemic and I'm wondering, like, from your perspective, what does that progression look like? Why is this year particularly worse than like last year?

Michael (he/him):

I think the interesting thing was in going through like the hybrid year, where we had half of our kids in the building one day and then they would switch out with the others, so you were teaching online while you were teaching students in the building at the same time, and it was this sort of the challenge of doing that and yet it wasn't. Living through it and looking back at it really wasn't that bad. It was just like trying to get used to the whole setup and you can make it work. And dealing with kids who are disengaged and seeing how much they disengage when they're home and then still being held accountable for that and it's like, well, but they're at home, I can't go through the camera and I've had students who are dialing in while they're laying in bed or they're dialing in from the shower and you're just like nope, sorry bye, like this is not something we need. But I think in the last two years, the amount that education has been politicized, but now even more so than ever, and the pushback of the idea of indoctrination and that you're teaching to try, and I'm like if we were indoctrinating your kids, we'd indoctrinate them, especially teenagers and probably middle schoolers to wear deodorant, older teenagers like lay off the perfume in the cologne. It's a little much. Why don't you show up on time? Why don't you stay off, like we would be indoctrinating them to that? not, you know all these other things you're worried about is doing it whether it's about being gay or whether it's about racism or any of those particular issues and agendas, it's like, no, that's not what we're doing. You know, and I think that breakdown, that lack of being able to have a civil conversation about what a parent wants for their child and what we provide in public education for them, and why it might not fit exactly what you want because it's not just about you, it's about the entire public that we're serving, and so constantly feeling like we're targeted and parents aren't coming to us to have a conversation, they're going online to have it, and that just opens up all of the insanity that is done online, and so you become the target for people from across the country. So I mean suddenly getting emails from strangers that are telling me how horrible I am and the terrible things that we're doing. You know, and especially like, if it's bad for me as a teacher or my fellow teachers in the department, it's 10 times worse for my department chair, who is really, you know, getting all the hate mail and to go through that. It's like it's just what are we doing this for? You know it's so. Then you go through a crisis where you have a lockdown or something like that and I'm like this is why this is happening, because we're getting threats in the school because you aren't doing. You know. You're putting everything online, You're opening the door for all these people to come at us and what do you think is going to happen? And then you want us to die for your kid, and it's like mm, yeah.

Bryan (he/they):

That's wow, you're good enough to die for my kid, but you're not good enough to teach them.

Michael (he/him):

Right, and I think that's what has made the last two years really so difficult.

Bryan (he/they):

Absolutely. I think it's frustrating also because there are political groups out there or individuals who are targeting teachers. And what drives me crazy is that there's this idea that you can just post like full on personal information online and then be not liable or accountable for the threats that happen to that individual person because you put their information online. And that's the part that really gets me where I think that there needs to be stronger laws when it comes to like doxing. People shouldn't be allowed to put your email address or your phone number or your address or even your school district on their TikTok account or Twitter X account and then have no accountability when it comes to the fact that their followers are now targeting you personally. And then that's the thing that gets me too is that we have to go into these lockdown drills because a school is getting a bomb threat based off of a lips of a TikTok post, right like, and then that person that runs that account does get zero accountability. Her followers get zero accountability because they made an anonymous phone call and now the school's on lockdown and that stuff. I think you're absolutely correct is that this heightened politicization of education has just made it almost impossible to just do your job.

Michael (he/him):

So we had an incident last year over a vocab list and a book that was being taught, or having a similar incident this year because the book is still being taught, and one of the things that happened was we all had to sit down and go over the controversial topics policy for the district and was being led by an assistant superintendent who was going through it and they were like let's list out what we call controversial topics and racism and LGBTQ plus. And over the course of the conversation I simply said so, with all due respect, what you're saying is that I shouldn't be an adult teacher. In fact, that's not what I'm saying. I'm like, but that is what you're saying. I said you don't realize. That's what you're saying. I don't think that you personally are intending to say that, but that is what you're saying. I said because you're listing me as a controversial topic. I'm not a controversial topic, that's just my life every day and that's offensive. It's offensive to me, it's offensive to students in here that you're telling them that they aren't like everybody else, they're controversial and so on, and that's a problem. And if your parents can't see that, shame on them.

Bryan (he/they):

And black teachers and Mexican teachers and anybody of color, and it's like if you're going to list these things as controversial topics, then literally what you're saying is that these people aren't okay, like we can only teach about white, straight people, and if they had their druthers it would be white, straight Christian people, and so I think the erasure in these policies from an administrative standpoint is probably not intended, but it's happening.

Michael (he/him):

Right. Whether they like it or not, and I said it afterwards because he got very emotional afterwards and he was talking to me. He said if something like that were to happen, I would lay down my job and I'm like that's not to be to say but would you, because I don't know? You're asking me to trust you and that's hard to do right now. And I said, and if it's not you, it certainly is the board, who certainly feels that way. So, and they're ultimately who we all work for. So maybe this isn't the district for me, and you have no idea how much that hurts to say.

Bryan (he/they):

Yep Parents if you are a parent who listens to this podcast, please run for your school board, because we need more folks who are willing to accept that different types of people exist and should be represented in the classroom bare minimum on the school boards.

Michael (he/him):

Or if you're a parent with a high school level of child, get an active PTA going where we start to have conversations again, because that's what's missing. And by high school, elementary school, you've got these vibrant, robust PTAs where parents are going in and making parties and doing cookies. In middle school they're still kind of fairly active, but suddenly you get to high school and there's really no PTA. There is, but they don't really do anything, or at least certainly not in my district. And they should. We should have a robust group that is a conversation between parents and teachers, and that way we understand them and we're on the same side. We're trying to do the same thing, it's just we're going about it in the way that we understand education. You're coming at it from a parent. We need to find ways to cooperate together.

Bryan (he/they):

Absolutely, and I would encourage people also that if you truly believe that there's indoctrination happening, don't take a meme or a picture or an online conversation as all of the truth. Go to the classroom that your kids are in and find out what's happening. As long as you're not disruptive, you'll be able to access the class Absolutely, and what you might find is a you might find a rainbow flag and zero conversation about it. Right, because that's not what we're doing at school. You're teaching English, I'm teaching theater, like that is what we do. We are teaching our core subject, not our political ideologies, and just because we have a flag up in our room doesn't mean that we're teaching and telling people. That's how it has to be. I mean, it's not like we're going in and being like you can only like Yankees because I have a Yankees flag in my room.

Michael (he/him):

Right.

Bryan (he/they):

Like there are so many colleges like, especially in Texas, all the like A&M versus UT's and all that stuff that happens like competitiveness. We're not going into the room and being like, well, in this classroom, you only like UT Austin. In this classroom, you only like A&M, Corpus Christi, Like that's not what it's about. It's about showing up and showing who you are as a teacher and just letting that live there and be there.

Michael (he/him):

They ask about my weekend. My husband and I did this and then we move on and they certainly don't seem to be thinking about it any more than I am. Sometimes they have more questions, like what's my husband do or stuff like that, but it's usually a very short conversation that we move on. It's like that we're here to work on literature, let's do our job right and yeah, I don't think that it's not this sort of like come and join the club. It doesn't work that way. I had a parent once to a student that come out to me and had been talking to me and they had told their parents when they came out to their parents that you know I've been talking to Mr Gagnon and the parent at one point wanted to know did I encourage it in any way? And then later had a conversation with the parent and I said it doesn't work that way. It's not. I said if it did, I said there would be thousands of suddenly gay children running around. It doesn't work that way. And I said I just am who I am and it gave him a comfort level to come and talk to me. I'm really proud of that and I'm really proud that he felt comfortable enough to do it and that got him to talk to you and that makes your relationship better and ultimately, that's the goal you know, and I don't again. I don't want them to feel ashamed about who they are. The first thing I always say when a student comes out to me is, like, the first thing you need to realize is you're okay. You're okay just the way you are.

Bryan (he/they):

There's nothing wrong with you.

Michael (he/him):

Nothing wrong with you, and this is your journey. You're going to figure out the way you want it to play out, and just know that I'm here if you need to talk it through, and that's it.

Bryan (he/they):

Absolutely. I mean, that's the thing that I think of and this circulates the internet a lot, you know, every couple of years. But if it were a choice, why would we choose the hatred and the targeting and whatnot Like? If it were truly a choice, what in your right mind thinks that someone would choose to live in all this animosity?

Michael (he/him):

Right.

Bryan (he/they):

And I think that it would be. I mean, this is a lot to ask for people to take a breath and use a little bit of logic to determine that maybe some of the things that they're saying aren't exactly logical.

Michael (he/him):

Right.

Bryan (he/they):

But again, why would I choose to be targeted by an entire religious group if I had the choice?

Michael (he/him):

But fear isn't logical. You know it's not. I'm also confused about what are you?

Bryan (he/they):

afraid of, because it's not like the straight people are dying, it's the queer people who are dying. What are you afraid of, straight people? You?

Michael (he/him):

know like Looking, of thinking that maybe you're wrong, maybe what you've learned is wrong. I mean, it's hard to. I think you know that's a big thing for parents is, and why I think the whole thing about that is you know why I think the whole thing about indoctrination and education is at such a high right now is the feeling like you're turning my kid against me and it's like education just gives people, you know, access to information. Ultimately, you know it's going to take them wherever it takes them. And the fact is like, well, every child sort of has a moment or a time where they are turned. They turn against their parents because they need to, they need to break free, they need to find out who they are. Eventually, that sort of weaves its way back into because you're their parent, like you know, the same way, my father made tons of mistakes, but he was my father. It was just sort of, you know it's the nature of the relationship.

Bryan (he/they):

I would love to like meet that person who's had the perfect parent child relationship their entire life, because I honestly feel like, as a parent, I'm like, oh, it doesn't exist.

Michael (he/him):

I have to say, despite all the issues, mine was actually pretty good. I mean, when I came out, my father was amazing, so I give him a ton of credit for a man who had only a high school education and was very self-taught. And when my brother told him, when I was shortly before my mother died, that I thought I was getting. He spent my adolescence reading everything he could get his hands on to try and understand, and so by the time I was ready to come out, he was like OK, you know when you come out, you're ready you're ready for the fight. You're ready to be like no, we're going to argue about this. And no, it was, no, it's OK. And I said no, if I'm dating someone, I want to bring them home. I want you to treat them the way you would treat my brother's girlfriend, or OK. And it's like, what do you mean? Ok, like I'm ready. I have my boxing gloves on and that's the way he was and it was. He was, you know, literally when he was dying and we were in the hospital, my husband was standing off to the side and he was like, you know, get in here, you're, you're part of this family and it's like that's very much who he was and I, you know, that's where I get my sensibility from, that's where I get my sense of empathy and care from some despite. You know, again I look at there are lots of things he was responsible for and made tons of mistakes, but, boy, when it came to the, to the really tough stuff he did, especially, you know, when I was coming of age, I think he made a lot of my mistakes with my older sibling. So I was like they might have a different take on him than I do, but but it was like yeah, you did it right for me and that you know that means everything, so that's awesome.

Bryan (he/they):

And that's it. And really, parents, that's what it is, is just being there for your child. And if you don't know something or something scares you like, just learn about it right because that knowledge and learning will. It will ease some of that fear, Right, and as a parent, you're always going to have fear I mean, that's just the nature of being a parent but like it'll lessen it to just learn a little bit about what you're worried about.

Michael (he/him):

And I think you know the separate is you've got ninety five to ninety nine percent of the parents that I really deal with are amazing. They're they're good, solid, good people and, yes, they have questions or we may have disagreements on things, but they're really good people and it's that small percentage that just they get. They get all of the air, they get all of the you know attention because they demand it and it just it's too bad that that sort of paints up a picture of parenting as a whole because they don't think in general. That's truly what it is.

Bryan (he/they):

And really you're right in that, like this five percent or even like one to two percent of parents, they get all the headlines. Yep, they are the loudest voice in the room and so therefore people think that they're the majority, but really it's like one to two percent of parents that we're having this issue with, and yet it's impacting like one hundred percent of minor minority teachers, right?

Michael (he/him):

Absolutely.

Bryan (he/they):

So thinking about that if you were to talk to a new teacher, someone going into the classroom for the first time, what advice would you give to them about being their authentic self in the classroom?

Michael (he/him):

I think that the key is always to remember it's your own journey and so you have to decide where you're at in that journey and what's going to work for you. Multiple things play into how your authenticity looks, because of what's the age of the children you're teaching, what's the environment that you're teaching in, what state are you in, what district are you in? Who's sort of, what's the political climate like in that area? And I think in the end you decide what your journey is. You make the steps that you feel like you're comfortable making and, as we were talking about earlier, if it isn't comfortable and it isn't working for you, then go somewhere else, find somewhere else to be, because you need to be in a place where you are going to be able to be your most authentic self, because that is going to inform the way you teach. You cannot teach in a guarded state all the time, and when you're that heightened, you're just not going to be a great teacher because you're not going to connect with students. And that feeling of disconnection just having it over the last couple of years was very jarring and very like how do I do this? Because I'm so guarded in the classroom because of what's happening around me, not because I'm suddenly not out, but because I'm just very aware of what's happening, and so I'm being mindful when I say things in a way that I usually don't. So now this year, I think I'm getting back into like I'm going to be me, and if people are going to come for me, they're going to come for me and I can't do anything about it. So I think, especially as a new teacher, those first five years are rough enough as it is. Choose the path that's going to allow you to have the most success and the most comfort, and let it be okay. Don't go by what anyone else says or what anyone else thinks that you should do or be. You know, in the end you'll decide what it is for yourself and what that looks like in your classroom. Just don't you know my one, don't, we, don't do anything that gives you a sense of shame.

Bryan (he/they):

That part right there, absolutely. And then what would you like to see the academic community do to be better support for LGBTQI plus students and teachers?

Michael (he/him):

I would like to see them be more vocal at this time in a meaningful way of creating conversation with real parents when I say real parents, I mean not that one or two percent who's turned it into the political agenda, even though they act like they don't, but with real parents and to really talk about how do we provide your child with access to an understanding of the diverse world they're going into, so that they have the empathy and the warehouse to navigate that world in a meaningful way that doesn't take away from their own experience and, at the same time, doesn't take away from anybody else's, because ultimately, that's what we want a society that allows people to live to their fullest potential, whether you agree with that path for them or not. So we need to find a better way of doing it and being vocal and pushing back and saying we're not going to cave on these particular things because they're wrong. It's one thing to have a conversation and say what alternatives do we have? I mean, as an English teacher, a parent always has the right to say I don't want my child reading that book. Okay, let's find an alternative. The best experience I ever had was a parent who said if you tell me what other books you could give them, I'll read them. And she read every single book that I said well, I thought maybe this book or this book or this book. She read them and came back and gave me great feedback on which ones would be great. And you know, it was just because the book we were reading just had some. A Holocaust book had just had some really graphic detail that I'm not trying to deny what it is to my child that we just don't do anything that's sort of rated R until they're 18. So if you could, I'm like we'll find something that's less graphic. Could you read these three books? And she read them and came back and we found a book that worked and that's what we did and it was like that's what it should be, and so we need to, and our administration and our academic peers need to be doing that work and creating those environments. And the same thing for parents, like I said, that active PTA of where we sit at the table and we talk about what are the concerns and what are the realities of education, because I often think a lot of your concerns about what happens in a classroom. You should come and stand in our hallways and in our libraries and in our cafeterias, and hear the way your kids talk and what they talk about and what they say to each other and the way they talk to teachers. Because if you think your kid doesn't know it, and even if your child is one of the ones who isn't saying it, they are surrounded by that all day long. And that's not even talking about social media, so that message has got to get out there about. Here's the reality of what your kids are really dealing with every day, because I don't think parents even have the slightest clue. And it's not because I think they want to be ignorant. I think it's simply because, like everybody else, they're going to work, they're trying to manage their lives, and so we need to do a better job of all around, of having those conversations and getting those conversations to happen, or else this is just going to continue to spiral.

Bryan (he/they):

Absolutely. There's so much packed into that that I just really appreciate. So I'm glad that this moment is here. So at this point I want to turn the mic over to you, and we always kept the interview with you asking me a question, so take it away.

Michael (he/him):

What made you go from being in the classroom to doing this?

Bryan (he/they):

Well, I chose to do this because I was having a hard time with conservative groups targeting me. I was the teacher of the year for my school district and a conservative, or what perceived conservative district, but again, it's like that one to 2%. But that one to 2% was also made up of very affluent people, and so I was being targeted because of that, in a way that my family, we moved to the district. I had thought I was going to be there for a long time. So we moved so that my daughter was across the street from her elementary school in the same school district and it got to a point where I needed to leave because I felt like if I'm being targeted at some point, it's going to be that my children are targeted. So I left the district and stood on this idea of I didn't have a place to share my story, and so I am now here, started the podcast a year later, because that place never popped up and I was like I'll give myself a year. If it pops up, I'll ask to interview. If it doesn't pop up, I'll just create it. And so I did, and part of it, like a part of this, is research based, like I am a theater pedagogy, but my research areas are universal design for learning, so making things accessible for everybody and queer theater, which means I do a lot of queer theory, and so part of this is that I just like information and I like talking with people and I like to present about I mean I have full on presentations about this podcast that I take to educational conferences talking about experiences that teachers have, and I'll you know, a teacher from Canada said this and it's very big stuff, but it's like these are the real life situations that queer teachers are experiencing in the moment. And I decided to take a break from the classroom one because moving to New York City has always been a dream of mine, and so when we moved here and my husband and I realized that we had the financial ability for me to move and kind of take a break and I have not taken a break since I was 18. I was like this is a chance. You know, I've been working hard for the last 20 years. This is a chance for me to take, I said, a school year. It turns out that I'm taking like five months because I like to work, I like what I do and so I have a position that I'll working at a university to do like technical direction for the theater department, which means I'm responsible for all of the lights, the sound, building sets, costumes, all those things, and that includes teaching the lab classes and their technical theater program. But I'll also have the opportunity to teach adjunct classes for theater education, where I get to kind of focus on that universal design for learning and how do we go teach these things in high school settings. And so I have always dreamed of working at a university and really thought that it was going to take a long time. I, like you, went into the corporate world it was just corporate entertainment and was there for 15 years before I started teaching five years ago, and so I got to what I wanted to do the long way, and now I get to do this and I get to do that, and it's kind of feeding two different sides of my personality and really filling a space that needed to be filled, because my goal is, in all of this chaos, that our voices will never be 100% silenced, because this podcast will exist and will continue to exist throughout all this kind of turbulent time. I think I used that term in my emails to people too. I was like do the turbulent nature of politics right now. You're welcome to be anonymous if you want, and we have some people who are going to be coming up on the podcast who are anonymous. Because these one to two percent of parents impact 100% of the minority, teachers and the nation and really around the world, because it's not isolated. The stuff that's happening here is happening other places.

Michael (he/him):

Right, I think people are often really shocked, especially in Connecticut. It's everywhere. It's not just, yes, you think Connecticut is a more liberal state, but it exists everywhere.

Bryan (he/they):

It exists everywhere and maybe it's just shifted slightly. There's certain like, for instance, you might find places where there's more anti-Semitic behavior as opposed to really racial disparity. These things are happening everywhere for any teacher in a minority situation. I've talked to teachers from France and Canada and I had a person who wanted to interview from Australia about our timing. Just never worked out, but in their pre-interview questions they said that they are dealing with the same situations we are dealing with in the US, in Australia. So it's really a worldwide problem that we're experiencing and unfortunately no one's found the solution. No one has the answer to how to fix it all. We're just kind of dealing with this rocky pendulum swing that hopefully will get back to a place where we're progressing towards inclusivity.

Michael (he/him):

Right In some way.

Bryan (he/they):

Yeah, absolutely. Hey, Mike, I really enjoyed our time today and I just want to thank you for being on the podcast and sharing your story.

Michael (he/him):

I'm really grateful that you responded and that I was able to be included, because I think it's really important, and I think the more, that we get our voices out there, like you said, and keep ourselves being heard and tell our stories and let one other educators know they're not alone who are going through it, that they have people they can reach out to, and that those who are thinking about going into it going into it with a little bit more of their eyes wide open but at the same time, know that they also have supports in place and they should demand supports as well.

Bryan (he/they):

Yep. So whoever you are, just know that you're not alone there. Especially in this virtual world that we live in, there is access to other people who will help support you.

Michael (he/him):

Absolutely.

Bryan (he/they):

Thank you all for listening at home. Have a great day. Thank you for joining us on this episode of Teaching While Queer. I hope you enjoyed it. If you did, make sure to subscribe, wherever you listen to your favorite podcast, leave a review, and that would help out tremendously. You can also support the podcast by going to www. teachingwhilequeer. com and hit support the show. Thanks so much and have a great day.

Michael Gagnon

HS English Teacher

As the seventh of nine children, I knew from an early age that I wanted to be an educator and that I was gay. During my adolescence, I put myself on hold just to get through some challenging times and did not come out until my early 20's. Rather than pursuing education, I followed by father's advice to enter focus on business since I came from a struggling low-income family. After spending nearly 18 years in the corporate world as an accountant, I finally followed my dream to become a teacher. I've worked in the public school system now for 16 years, beginning my teaching career in a Hawai'i Title I school before returning to the East Coast and teaching a suburban high school.

Coming of age in the midst of HIV and AIDS in the mid-80's kept me fearful and hesitant for a long time. However, by the time I started teaching, I had come into my own and despite the risks, found that I could only be a good teacher if I was authentic, which meant being out. That's the way I live and teach.